It took my parents many years to die. My father had an “indolent” lymphoma, an adjective which could not be more apt for my family (we are all homebodies); and my mother had a progressive neurodegenerative disease with all the symptoms of ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, aka Lou Gehrig’s Disease), but not ALS. My father’s trajectory towards death was less pronounced than my mom’s, but he was subject to plenty of horrors which I will not describe here.

It was my mother’s dying that was the more tragic, in my mind, because of her relative youth and loss of opportunity for her to enjoy things that she had come to yearn for, expecting to enjoy a time when she could pursue them more easily. It was not to be. My father, when I asked him, professed to being ready to die, lucky to have had the life that he had lived in exactly the way he had wanted to live it. My mother was just cheated, and cruelly. First to fail was her motor control: her ability to walk, keep her balance, then hold a pen or use her hands. After losing general control over her body movement she lost her senses one by one, first a precipitous loss of speech due to an emergency tracheostomy, then her hearing, sense of taste, touch… Untouched was her memory, her wit, her intellect, and she became increasingly trapped and isolated within her failing body, her mind as sharp as ever; it seemed to me, and probably to her, that she was being buried alive. She never complained. The closest she ever came, in my hearing, to touching upon her feelings on what her life had become was what she told me when I was wheeling her home from a park one wintry day: “I’ve learned to be patient”.

I’d visit her and my dad as frequently as I could with two children still in elementary school. In fact, one of my trips back East to see my mom (my dad had died three months previously) preceded a overnight school trip by my daughter’s 4th grade class to a First Nations Longhouse. I had volunteered to be a parent chaperone/helper on the trip which was to happen two days after I returned from seeing my mother. I take my commitments seriously and, barring any drastic change in my mother’s condition, I was going on that trip. This post doesn’t take us on the trip, but I’m including a couple of photos below that reflect the experience I had at the Longhouse:

But this is in the future, and we are still in Vancouver, before my trip to see my mom, before our trip to Squamish. I am going to see my mother and provide respite care for my sisters and crisis management for my mother.

Shell-Shocked and Sleepless: The Perfect Chaperone for an Elementary School Trip

Then, I did go to see my mother, and I returned. Back in the schoolyard the day after my return, the principal at the time – a very genial man with a sense of humour that seemed to match my own, elements of darkness included – approached me and asked me if I was still able to serve as a parent chaperone on this school trip.

“Of course,” I replied, “I wouldn’t miss it.”

I was not looking as peart as I might; my two-week-long caregiver’s diet of KitKats and my sister’s coffee, coupled with a general lack of sleep, must have showed because he then asked me, “How are things going with your mother?”

I told him the truth, that my mother’s decline was a puzzlement to me, that ‘just when I think that she can’t get worse, she gets worse. I can’t imagine how or when things are going to end.”

He expressed sympathy and then shared the following story with me. Even if you’ve heard it, please read it again.

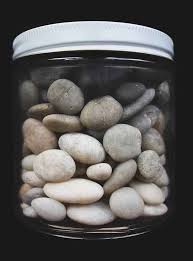

A teacher walks into a classroom and sets a glass jar on the table. He silently places 2-inch rocks in the jar until no more can fit. He asks the class if the jar is full and they agree it is. He says, “Really,” and pulls out a pile of small pebbles, adding them to the jar, shaking it slightly until they fill the spaces between the rocks. He asks again, “Is the jar full?” They agree. So next, he adds a scoop of sand to the jar, filling the space between the pebbles and asks the question again. This time, the class is divided, some feeling that the jar is obviously full, but others are wary of another trick. So he grabs a pitcher of water and fills the jar to the brim.

At this point, this very kind man in the person of my daughter’s principal stopped, looked at me and said in a very comforting tone, “You see, even when we think we don’t have the capacity to take any more, we find that there is always room for more.”

I replied to his kind words in a rather sardonic tone, “Oh, I thought you were telling me that I might have to end up drowning my mother.”

It was a pretty black attempt on my part to be funny, and he just looked at me for a long moment before walking away. Sometimes there really is no help for us twisted ones.